Book Giveaway Contest Click on the link and enter for a chance to win a copy through Goodreads!

75 years have gone by since Germany's armies crossed the Polish border, Sept. 1, 1939, the official start of World War II. My father, who had been imprisoned and released from a Nazi prison in Brno, Czechoslovakia, soon found himself on a one-way cattle car ride to the German-Soviet demarcation line.

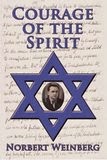

This essay, taken from the book, Courage of the Spirit, recounts the events of the first months of World War II as seen from the perspective of a Jewish refugee fleeing the Nazis.

First Stop, Lwów

Lwów,

with its western European influence, has been dubbed the “Little Paris of the

Ukraine.” It has a long history as a major center of culture in then Poland and

now Ukraine. It could also have been called the Little Paris of Poland, or of

Austro-Hungarian Galicia and Lodomeria, as well, as it was passed to different

rulers repeatedly. It has been renamed many times since its founding in the thirteenth

century by King Daniel of Halych (Galicia) in honor of his son, Lew. Lwów is

the City of Lions; hence, the many lions that appear on city seals and motifs

in Lwów literature. Under the Austrians, it became Lemberg and took on a

decidedly German flavor. Lemberg remained a popular name, as my father referred

to it by that name decades later. With the independence of Poland after WWI, it

became Lwów, then, under the Soviets, Lvov, and now, under the Ukrainians,

Lviv.

The

varied names reflect the particular tensions among the resident populations

over the years, a mix of ethnic German, Polish, and Ukrainian. In the midst of these

groups dwelt a large Jewish population, some 140,000, almost 30 percent of the

total population. Of this large number, only two or three hundred would survive

the Holocaust.

As

I recounted in previous chapters, my uncle Munio had managed to buy his way out

of Czechoslovakia by train to the nearest destination heading east in which he

felt safe—the city of Lwów. Shortly thereafter, when the Germans invaded

Poland, my father was expelled, as were numerous other non-Czech Jews, to the

new ceasefire lines facing the Soviets, who now sat on the eastern half of

Poland.

The

first days of the German invasion were carried out with the lightning-strike

swiftness that would come to mark the style of future German warfare—the

blitzkrieg.

On

September 1, 1939, the Germans dumped the bodies of dead concentration camp

prisoners dressed in German army uniforms at the Gleiwitz radio station on the Polish

border and declared that they had been viciously attacked by the Polish army.

With this pretext, the Nazis rushed in with tanks and dive-bombers against an

overwhelmed Polish military of infantry and cavalry. The Poles put up a stiff

resistance and counted on their allies, the British and the French, who had

assured the Poles that they would not tolerate the demolition of a free nation

as they had tolerated the devouring of Czechoslovakia. However, the German

blitz was as its name implies, and Poland’s allies could not mount a

counteroffensive in time. By September 6, Krakow had fallen, and by the sixteenth,

Warsaw was fully surrounded.

On

the seventeenth, the ultimate betrayal took place—the Soviet forces invaded

Poland from the east, so that Poland was now caught in a vise. Three days

later, German and Russian forces met at Brest-Litovsk, and by September 21, the

Soviets had taken Lwów.

A

mere twenty-eight days after the outbreak of hostilities, what was left of the

Polish government fled to exile in France. Poland, as a country, ceased to

exit.

The

Soviets claimed that they had rushed in to protect their Ukrainian brethren in

Poland. That was but a thin pretext, as they had carved up Poland with the

Germans shortly before the outbreak of fighting, in the Molotov-Ribbentrop

pact. Poland’s clock was set back a century and a half to the time when Poland

had first been carved up by the Prussians, Austrians, and Russians.

It

has become clear, in the perspective of history, that Russian imperialism drove

the Soviets, despite their claim to have shucked off that mentality in their

quest to attain a communist state. They never made peace with the concept of a

Poland that had gained its freedom in the aftermath of World War I; they still

smarted from the brief war with Poland after that independence. They rounded up

some of the cream of Polish military and political leaders and summarily

executed them in the Katyn forest in the spring of 1940 to guarantee that none

would remain to contest their hegemony.

In

the first days of the cessation of fighting, the line of demarcation was fluid

and ill defined. As I mentioned in the previous chapter, my father was rounded

up and put on a train with other Polish Jews from Brno, and all of them were

sent to what amounted to a no-man’s land. The original plan, concocted by

Eichmann, was to establish a Jewish reservation.

In

the confusion following the opening days of the war, however, my father, like

many other refugees, was able to get away from the German captors on the one

side and from the Soviet liberators on the other and make his way to the

nearest major city, Lwów, where his brother awaited him.

There

was another benefit for the brothers in heading to Lwów: family. They had both been

born in Dolina, some forty miles to the south, so they were familiar with the

region; my uncle, after all, had been traveling frequently to the region on

business. Even more directly, they had second cousins, Irene and Karol

Gottdenker, through a common great grandfather.

As

I wrote in an earlier chapter, my father’s grandfather, Moses Zarwanitzer,

through his first wife, was great-grandfather to Irene. Her father, Norbert

(Nachman) Gottdenker, was in Dolina as well, and had worked in the lumber

business for his and my father’s cousin, Judah Zarwanitzer. Later, when my

father was a young man of thirty living in Vienna, Norbert Gottdenker and his

wife Helena had come to visit with their young children Irene and Karol, who

were ten and nine at the time. By 1939, when my father and uncle showed up in Lwów

as refugees, they were aged thirty-eight and forty-one, hardly of romantic

interest to the young and vivacious seventeen-year-old Irene. (Seven years

later, they would meet again under different circumstances.) At some point,

they must have told their relatives what had transpired in Germany, Austria,

and Czechoslovakia and to be prepared in case the Germans turned on their

Soviet allies—a likely possibility, if the Germans’ decisions in the recent

past were any indication.

The

Soviet occupiers needed to come to grips with governing not only their newly

liberated Poles and Ukrainians but also with handling the needs of so many

refugees that had now come into Lwów. Well over 100,000 Jews had made their way

there along with countless others fleeing the German occupiers in western

Poland. This presaged the beginning of the largest waves of mass migrations in

any time in history, numbering in the tens of millions, in Europe and Asia, throughout

the following decade.

Beyond

the logistics of feeding and housing so many was a political concern: many of

these refugees were politically active socialists, Zionists, and communists—true

believers whose ideals of communism did not match the reality of the Stalinist

system. All of these posed a potential threat to a paranoid regime. (It is

interesting to note that in 1940, the leading communist opponent of Stalin,

Leon Trotsky, was murdered in distant Mexico, and Menachem Begin, a Zionist

leader, was arrested as an agent of “British Imperialism.”) The last thing that

the regime could tolerate was an infestation of problematic political refugees

on the border with their temporary German allies. Hence, the Soviet police

rounded up refugees for transportation to the far eastern regions of the Union

such as Siberia or Central Asia. My father and uncle were caught in the roundup

and herded to the train station to be boarded on cattle cars for destinations

east.

Nothing

was well organized at this time, and the numerous refugees included families

with children that needed to be fed. An officer in charge let a few leave to

buy some food, relying on them to return faithfully to their children. My father

and his brother sensed an opportunity and volunteered to fetch water. The

official in charge of this impromptu encampment sent a soldier to follow them

to make sure they returned. The two intentionally kept going off route, first

to the right, then to the left, getting lost intentionally, until the guard became

frustrated with them and shouted, “How stupid are you?” My uncle Munio pleaded

with him. “You have been posted here before; surely, you know the way better

than we do. Why don’t you lead, and we’ll follow you.” The guard, weary of

herding them, marched ahead of the two brothers. As they approached the next

wall, Willi and Munio jumped over the railing without the guard paying notice,

and they made it into the city. They had left behind whatever meager

possessions they had managed to save at the camp; these would better serve some

other refugees.

This

bought them more time. They continued to improve their mastery of chemistry,

particularly in the field of chemical engineering, as this would be their only

means of support in a regime that had no room for businessmen, attorneys,

Zionists, and students of political science, and certainly no room for rabbis. Lwów

was still too full of refugees, so the Soviets initiated massive deportations

in June of 1940. They once again caught the two brothers in their dragnet. The

brothers had hoped to go to Stanislawow (now Ivano-Frankivsk), as it was the

regional capital for their hometown of Dolina. They were sent off to Tarnopol

instead. This was, unknown to them, a boon, as it was much nearer to the Soviet

border and a future route of escape. They had another year during which they

could better understand the strategies for survival under the Soviet system.

When the Germans advanced in the summer of 1941, they headed post-haste to a

place the German forces would never reach: Stalingrad.